- Screening for Colon Cancer

- Barrett’s Esophagus

- Pancreatic Cancer

- Pancreatic Cysts

- H. pylori and stomach cancer

- Celiac

- IBD

Colorectal cancer is the third most common type of non-skin cancer in both men (after prostate cancer and lung cancer) and women (after breast cancer and lung cancer). It is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States after lung cancer. Although the rate of new colorectal cancer cases and deaths is decreasing in this country, more than 145,000 new cases were diagnosed and more than 49,000 people died from this disease each year over the past 5 years.

The exact causes of colorectal cancer are not known. However, studies have shown that certain factors are linked to an increased chance of developing this disease, including the following:

Age

Colorectal cancer is more likely to occur as people get older. Although this disease can occur at any age, most people who develop colorectal cancer are over age 50.

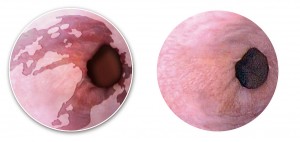

Polyps

Polyps are abnormal growths that protrude from the inner wall of the colon or rectum. They are relatively common in people over age 50. Detecting and removing these growths may help prevent colorectal cancer.

Personal History

A person who has already had colorectal cancer is at an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer a second time. Some women with a history of ovarian, uterine, or breast cancer have a higher than average chance of developing colorectal cancer.

Family History

Close relatives (parents, siblings, or children) of a person who has had colorectal cancer are somewhat more likely to develop this type of cancer themselves, especially if the family member developed the cancer at a young age.

Ulcerative Colitis or Crohn’s Colitis

People who have ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis are more likely to develop colorectal cancer than people who do not have these conditions.

Diet

Some evidence suggests that the development of colorectal cancer may be associated with high dietary consumption of red and processed meats and low consumption of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.

Exercise

Some evidence suggests that obesity and a sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Smoking

Increasing evidence from epidemiologic studies suggests that cigarette smoking, particularly long-term smoking, increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

Screening and Its Importance

Screening is checking for health problems before they cause symptoms. Colorectal cancer screening can detect cancer, polyps, nonpolypoid lesions,(flat or slightly depressed areas of abnormal cell growth) and other conditions. Flat or depressed lesions occur less often than polyps, but they may have a greater potential to develop into colorectal cancer. Finding and removing polyps or other areas of abnormal cell growth is the most effective way to prevent colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer (like most cancers) is generally more treatable when it is found early.

The following tests are available for colorectal cancer screening:

Colonoscopy

Virtual colonoscopy

Double contrast barium enema

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT)

You should talk to Dr. Robbins about when to begin screening for colorectal cancer, which test to have, the benefits and risks of each test, and the frequency of testing.

If you have chronic acid reflux or frequent heartburn, you are at risk for a condition called Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the lining of the esophagus, the swallowing tube that carries foods and liquids from the mouth to the stomach. Left untreated, it can in rare cases lead to cancer of the esophagus. About 3.3 million American adults have Barrett’s. Dr. Robbins specializes in the diagnosis, management and, if needed, endoscopic treatment of this condition.

If you have chronic acid reflux or frequent heartburn, you are at risk for a condition called Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the lining of the esophagus, the swallowing tube that carries foods and liquids from the mouth to the stomach. Left untreated, it can in rare cases lead to cancer of the esophagus. About 3.3 million American adults have Barrett’s. Dr. Robbins specializes in the diagnosis, management and, if needed, endoscopic treatment of this condition.

Pancreatic cancer arises when cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control to form a tumor. These cancer cells have the ability to invade or spread to other parts of the body. There are a number of types of pancreatic cancer. The most common, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, accounts for about 85% of cases, and the term “pancreatic cancer” is often used to refer only to that type. These adenocarcinomas start within the pancreatic glands which make digestive enzymes. Signs and symptoms of the most common form of pancreatic cancer may include yellowing of the skin or eyes, unexplained significant weight loss, light-colored stools, dark urine and loss of appetite. There are usually no symptoms in the disease’s early stages, and symptoms that are specific enough to suspect pancreatic cancer typically do not develop until the disease has reached an advanced stage. By the time of diagnosis, pancreatic cancer has often spread to other parts of the body.

Pancreatic cancer rarely occurs before the age of 40, and more than half of cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma occur in those over 70. About 25% of cases are linked to smoking, and 5–10% are linked to inherited genes. Pancreatic cancer is usually diagnosed by a combination of medical imaging techniques such as MRI or computed tomography, blood tests, and examination of tissue samples (biopsy) with endoscopic ultrasound.

Pancreatic cysts: Pancreatic cysts (fluid filled pockets) are diagnosed with increasing frequency because of the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging, like CT and MRI scans, or even traditional abdominal ultrasounds. Pancreatic cysts may be detected in over 2 percent (2 out of 100 people) of patients who get scans for reasons not even related to the pancreas, and this frequency increases with age. Identifying pancreatic cysts is important, since some have malignant, or cancerous, potential. Dr. Robbins has special training in a technique called endoscopic ultrasound that is used to detect, diagnose and manage the many different of cysts that can affect the pancreas.

Gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death in the world. In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) declared H. pylori a group I human carcinogen for gastric adenocarcinoma; in other words, this commonly found gram-negative spiral bacteria is a major cause of stomach cancer. H. pylori can cause chronic active gastritis and atrophic gastritis, two conditions that are the early steps in the cancer development sequence. Infection with this bacteria can be diagnosed in a number of ways (blood, breath, stool and endoscopy-based tests) and eradication of H. pylori appears to reduce the risk of gastric cancer in high-risk populations. Fortunately, only a minority of infected individuals will develop gastric cancer. Dr. Robbins can discuss which test, if any, is appropriate for you.

A number of studies have noted a small absolute increase in overall mortality (death) in patients with celiac disease compared with the general population. The association appears to be strongest for lymphoma and gastrointestinal cancer. Whether the degree of compliance with a gluten-free diet influences the rates of cancers is not known. For the vast majority of patients with celiac disease, a digestive cancer is no more likely to develop than in someone without celiac disease.

The risk of colorectal cancer is increased in ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease. There is agreement that patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) should undergo surveillance colonoscopy, although an iron-clad reduction in mortality due to surveillance (periodic checks with colonoscopy) has not been clearly established. Patients with ulcerative colitis who have pancolitis (colitis involving the entire colon organ) should begin surveillance colonoscopy after eight years of disease and colonoscopy should be repeated every one to three years. Patients with Crohn’s colitis probably have the same risk of colorectal cancer as those with UC, and should also undergo surveillance with colonoscopy.